NTSB

Safety Spotlight: VFR into IMC

VFR into IMC accident investigations by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) continually cite poor decision making as one of the main reasons pilots find themselves in these situations. Unlike other accident causes (e.g., mechanical failure), VFR into IMC usually does not occur instantly. Pilots either had the tools necessary to know the conditions ahead of time or should have recognized the worsening weather conditions. Failure to act or react to changes in conditions has continued to drive the high fatality rate. To understand this type of accident we need to review the fatal accidents contained in the NTSB data.

The NTSB classifies VFR into IMC accidents differently than the Nall Report, but numbers are similar across both sources. The NTSB uses the term “unintended flight into instrument meteorological conditions” (UIMC), which is in the list of top five accident causes.

A subset of UIMC, and the majority of fatal accidents in the category, VFR encounters with IMC are traditionally thought of as VFR into IMC. Confusing, perhaps, but the differences are minimal, relating mainly to how each organization names the cause. We will simply refer to this accident type as VFR into IMC.

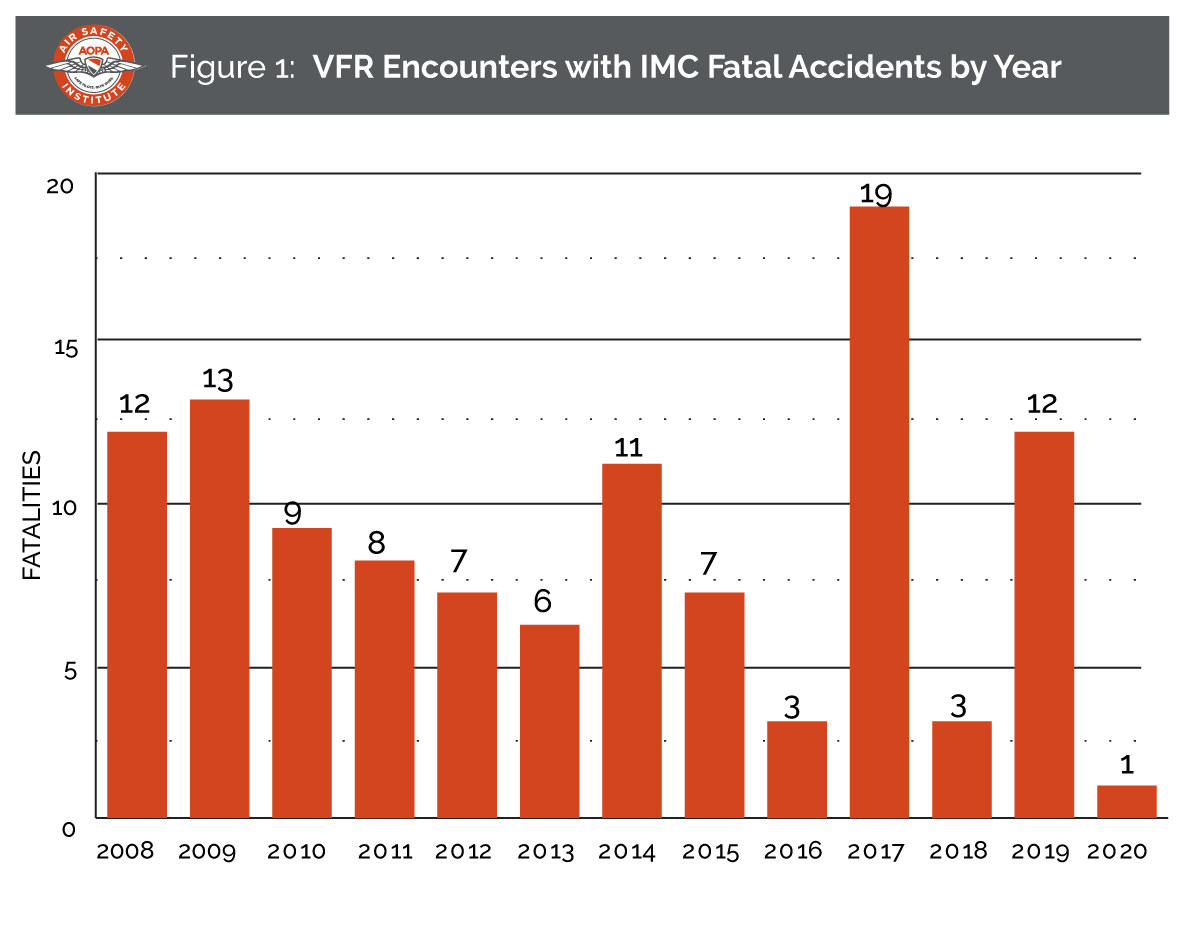

Breaking down NTSB data, there were 111 fatal VFR encounters with IMC accidents from 2008 through 2020 (see Figure 1).

Phase of Flight

More than 70 percent of VFR into IMC accidents occurred during the en route phase of flight (see Figure 2). More disturbing were those accidents that occurred on takeoff and initial climb. Twelve percent involved pilots, who, shortly after becoming airborne and attempting to reach cruising altitude, encountered conditions that led to a fatal accident. Failures in decision making and loss of situational awareness, along with a blatant disregard for the dangers imposed, are high for pilots who elect to depart in these conditions. Maneuvering and approach make up the rest of the accident phases. These fatal accidents are mostly preventable, and while conventional wisdom states that these pilots failed to properly understand the weather, the data suggests that the argument is much more complex. The first step in mitigating these accidents should be a comprehensive weather briefing since VFR into IMC accidents correlate highly with weather.

Figure 2: Fatal Accidents by Phase of Flight

|

Phase of Flight |

Number of Fatal Accidents |

Percentage |

|

Enroute |

79 |

71.2% |

|

Maneuvering |

13 |

11.7% |

|

Initial Climb |

11 |

9.9% |

|

Approach |

5 |

4.5% |

|

Takeoff |

3 |

2.7% |

Weather Briefings

The NTSB often struggles with determining pilots’ preflight weather briefing status, due in large part to few sources officially recording the instance pilots accessed the information. And while regulations do not require pilots to use only these recorded sources, the NTSB leans toward “Unknown” in cases where there is no clear evidence.

Preflight weather briefings alone are no guarantee of preventing VFR into IMC accidents. Several accidents from the dataset above involved pilots who called weather briefers throughout the day for an updated picture of the weather. The fact is that conditions change from the time pilots receive a briefing to the time they arrive at the weather. Constantly updating the weather picture along the route of flight becomes more critical and a better means of prevention against these types of accidents. Even then, pilots are susceptible to in-cockpit datalink latency (i.e., the interval between processing the weather data to its display on the cockpit device) and rapidly changing conditions. Several accident reports note changes in conditions along the route of flight, which suggests pilots were unable to properly prepare and actively avoid these conditions.

Constantly updating the weather picture along the route of flight becomes more critical and a better means of prevention against these types of accidents.Conditions

For VFR into IMC accidents to occur, the aircraft must enter IMC, but the prevailing conditions are not required to be IMC. In these cases, it’s best to think of aircraft entering cloud layers with visual meteorological conditions (VMC) existing below and/or above the aircraft. While some accidents involved pilots becoming trapped above weather, others indicated pilots who flew into or continued flight in deteriorating conditions. With most accidents occurring in daylight conditions (69 percent), inadvertent entry into IMC seems impossible (see Figure 3). Flying during twilight (14 percent) and night (12 percent) conditions can increase chances of inadvertent entry since it could be difficult to see clouds, but twilight and night are not where most accidents occur. It’s worth pointing out that entry into clouds is one type of VFR into IMC accident, but reduced visibility due to rain, mist, fog, or haze can also make it difficult to maintain positive aircraft control.

Figure 3: Light Conditions

|

Time of Day |

Number of Fatal Accidents |

Percentage |

|

Day |

77 |

69% |

|

Twilight |

15 |

14% |

|

Night |

13 |

12% |

|

Dusk |

3 |

3% |

|

Unknown |

2 |

2% |

|

Dawn |

1 |

1% |

Reduced visibility can create a more difficult scenario for pilots than a ceiling or cloud layer, which can provide a false sense of security. Flying in reduced visibility can create several visual illusions, but primarily the conditions obscure the horizon. Reduced visibility, along with a belief that the weather is going to improve on the other side, has lured far too many pilots to push ahead, resulting in fatal accidents. Furthermore, the continuation of flight draws pilots in deeper as they hope to break out, preventing a fast and immediate exit.

All pilots are susceptible to poor decision making. It’s tempting to assume pilots involved in these accidents justified their reasons for going instead of relying on the wealth of information and data that would strongly suggest delaying or canceling. One such accident involved a pilot who was unable to see the taxiways due to poor visibility. The pilot requested assistance from ground personnel in navigating to the runway. Shortly after takeoff the aircraft became airborne before crashing in the middle of a field, where a post-crash fire consumed the plane. A family lost their lives all due to a pilot’s desire to depart. Post-accident discussions resonate the pilot’s complete disregard for the rules, but how many pilots have departed thinking the fog would burn off soon or it’s safe because the visibility is unrestricted once off the ground? And how many pilots have been pressed for time or a desire to get to their destination? The benefit of hindsight should make all pilots realize their vulnerabilities instead of casting judgment.

Launching in weather below minimums leaves almost no option for properly handing an emergency after takeoff. After all, where would you go if the runway is barely visible or completely hidden? In the case above, the pilot lost control of the aircraft, and with no visual clues on the ground, he was unable to keep the plane in the air. When departing in low visibility, pilots should consider what they will do should the need arise for an emergency landing. Taking off into better weather seems logical and is a safer option for several reasons. The need for a clear visual picture is paramount during the takeoff roll, as many of the inputs necessary to control the aircraft at low speed are almost exclusively provided visually. Countering drift and maintaining runway alignment are almost entirely a visual maneuver. Reducing the sight picture leads to a reduction in detection and time to correct. These compound the difficulty and increase the likelihood of a negative outcome, especially in the event of a takeoff emergency. But what about those accidents where pilots were prepared for the weather?

Flight Plans

Five percent of all fatal VFR into IMC accidents were on IFR flight plans (see Figure 4). Pilots and aircraft that are legally allowed to fly in these conditions still fall victim. These are pilots who had air traffic control (ATC) services available to them and, ideally, had a sound understanding of the weather; however, even with many pilots electing not to file a flight plan (81 percent), the use of ATC is mixed among the accident reports. Based on radar plots and queries with pilots, there are cases where ATC recognized the initial signs of a pilot losing sight of the horizon. In some cases, these pilots requested assistance from ATC. Notably, few accidents even mention the pilots declaring an emergency, which all these situations warrant. In challenging conditions, several of the accidents had ATC services available and the pilot elected not to take part. Perhaps experience can help prevent these accidents.

Five percent of all fatal VFR into IMC accidents were on IFR flight plans.ATC's Role During an Emergency

Can ATC declare an emergency for a pilot? Watch this video to learn more.

Figure 4: Accidents by Flight Plan

|

Flight Plan Filed |

Fatal Accidents |

Percentage |

|

NONE |

90 |

81% |

|

CVFR |

6 |

5% |

|

VFR |

6 |

5% |

|

IFR |

5 |

5% |

|

Unknown |

4 |

4% |

Certificate Levels

Experience and ratings show that instrument-rated and high-time pilots are still susceptible to VFR into IMC accidents, with the majority (62 percent) holding a private pilot certificate and more than 20 percent of them having an instrument rating (see Figure 5). Across the entire dataset, nearly one third of all pilots hold an instrument rating. Concerning is the reversal of accidents for instrument-rated commercial and ATP pilots. While all ATP pilots hold an instrument rating, accidents involving commercial pilots with instrument ratings outpace their non-instrument-rated counterparts two to one—16 and eight respectively.

Figure 5: Fatal Accidents by Certificate and Rating

|

Certificate |

Instrument Rating No |

Instrument Rating Yes |

Unknown |

Grand Total |

|

Private |

60 |

13 |

|

72 |

|

Commercial |

8 |

16 |

|

24 |

|

ATP |

|

6 |

|

6 |

|

Student |

3 |

|

|

3 |

|

Sport |

2 |

|

|

2 |

|

Unknown |

|

|

3 |

3 |

These statistics suggest that rating alone is no guard against this type of accident. Well known and discussed at length among aviators is the value and importance of proficiency versus currency (the latter referring to the flight review and recent flight experience requirements outlined in 14 CFR 61.56 and 61.57, respectively). While the difference can be difficult to measure, the overriding concern is that pilots should still have a basic understanding of how to avoid these conditions. The accident investigations of these pilots struggle to determine proficiency and, at time, currency. The common belief is that pilots who are no longer current make up this entire dataset, but there are still accidents where pilots were current. At a bare minimum these pilots are expected to avoid or escape IMC before becoming a statistic. Additionally, in a few of these accidents a second pilot-rated passenger was aboard. This second pilot could and should have provided some assistance or at least spoken up when they saw poor decision making occurring.

Insidious Nature

Unlike many other accident causes, VFR into IMC is not the last sequence of the accident. It can be the defining event or main cause of the accident, but an aircraft does not stop flying simply because it encountered IMC. Yet the cause of the accident was this encounter. A defining event is an event that, if it did not occur, the accident would also have not occurred. Eliminating the defining event prevents the accident. In the data above, the defining event was VFR into IMC, and specific to those accidents if the encounter was avoided the accident would not have occurred. However, those accidents only partially tell the story of the dangers of VFR into IMC.

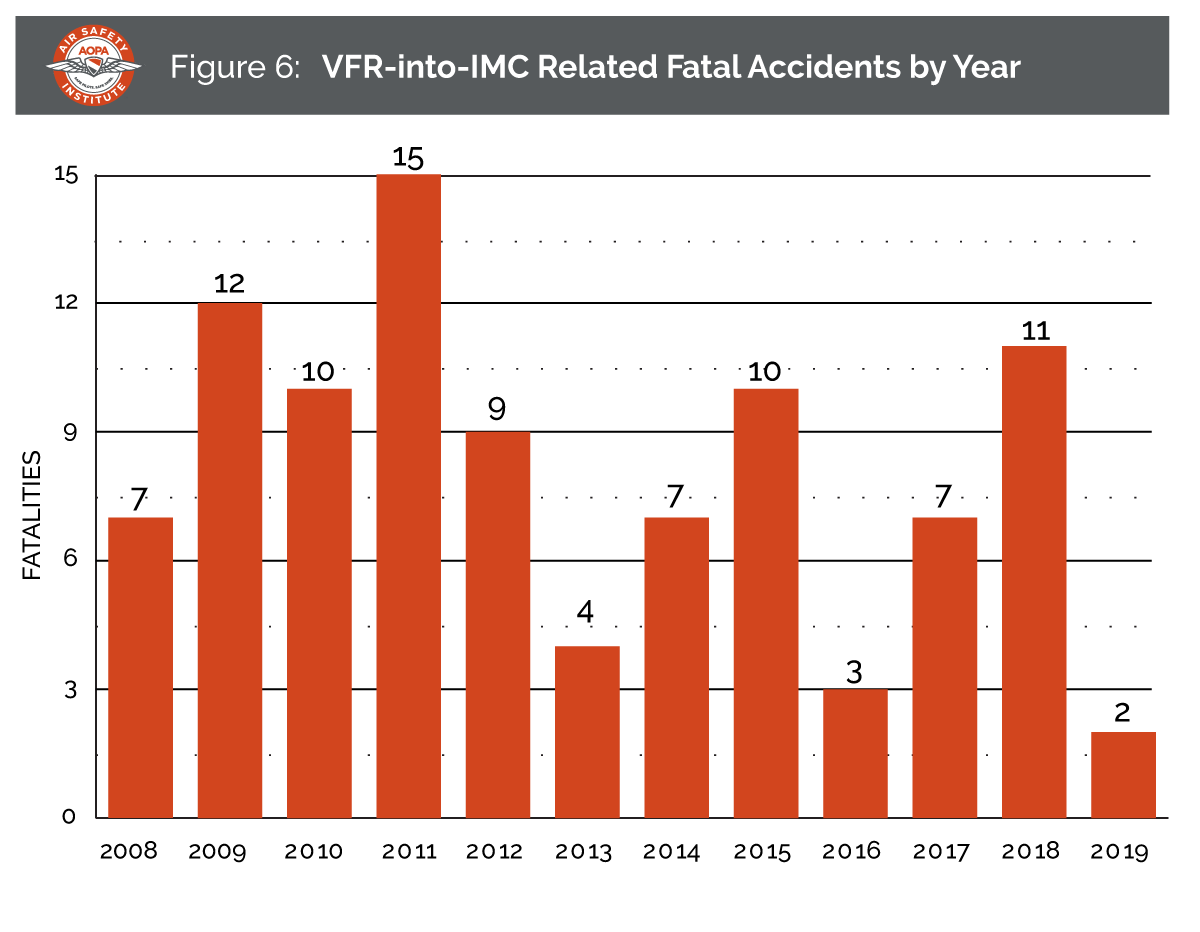

VFR into IMC is insidious and routinely seen as a contributing factor in loss of control (LOC), controlled flight into terrain (CFIT), fuel-related and occasionally mechanical failure accidents. Of the 111 fatal VFR into IMC accidents, an additional 97 (see Figure 6) involved VFR into IMC as a factor. Of those 97, 49 were LOC and 37 were CFIT. The dangers are ever present, and while actively flying unprepared into IMC may not result in a fatal accident, the likelihood certainly increases.

VFR into IMC is insidious and routinely seen as a contributing factor in loss of control (LOC), controlled flight into terrain (CFIT), fuel-related and occasionally mechanical failure accidents.

While fatal accidents are always tragic, not all VFR into IMC encounters end fatally. Reports from pilots who survived a VFR into IMC encounter and were not involved in an accident could provide insight into how to escape and what to look out for. These reports are voluntarily submitted by pilots and collected and analyzed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).