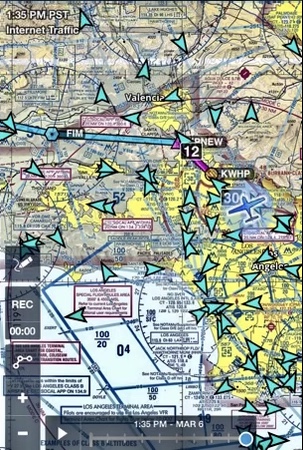

As usual Mother Nature gave me some real-world experience which challenged my own personal minimums on a recent flight. I head to the Pacific Northwest monthly for business. Having my own personal time machine has allowed me to realize the dream of living and working in two very different states.

Planning for a 4.5-hour trip over some beautiful but inhospitable terrain is a challenge. With no de-icing or anti-icing systems on my vintage Mooney, weather can be a friend or foe. For

this trip 30-35 knot headwinds were forecast at my “normal” altitude of 10,500-12,500. Typically, I leave my fuel stop in Northern California and climb right up to cruising altitude. Due to the forecast winds I decided to fly low

until reaching Redding, CA, then up and over the terrain.

Planning for a 4.5-hour trip over some beautiful but inhospitable terrain is a challenge. With no de-icing or anti-icing systems on my vintage Mooney, weather can be a friend or foe. For

this trip 30-35 knot headwinds were forecast at my “normal” altitude of 10,500-12,500. Typically, I leave my fuel stop in Northern California and climb right up to cruising altitude. Due to the forecast winds I decided to fly low

until reaching Redding, CA, then up and over the terrain.

This might not sound like a big deal to many pilots, but altitude has always been my friend and I like the options it affords me, should I become a glider. With this in mind I opted for the northwesterly course around Mt. Shasta. This flight plan, while not the most direct route, puts me very near Redding, Weed, Dunsmuir and Siskiyou airports. I have to say that at 8,500 feet I got a great view of the terrain, and the ride was smooth as silk. However, this was a calculated risk, based on my personal guidelines.

It hasta be Shasta

My goal in writing this series is that as PIC you do everything in the airplane intentionally and with forethought.

So here we go. In the past few months, we began our journey into the mindset needed for the functional implementation of minimums. As I pondered personal minimums in a pandemic, I reached in to my address book of pilot friends to ask questions about minimums, guidelines, self-restrictions and the like. I spoke to range of folks from pretty newly minted private pilots, to those working on an instrument rating, commercial, CFI and DPE. I talked with female and male pilots with hours ranging from low hundreds to 25,000. As one CFI/DPE pondered in regards to minimums…

How far do I put my head in an alligator’s mouth before I can’t get it out?

I had a fabulous time talking with a baker’s dozen pilots and I got a little gem or a pucker factor from each of the conversations. My hope is that our words might start an honest discussion on ways that we can keep ourselves safe in the airplane or on the ground. Because in the end, cheating on your minimums is cheating yourself.

This series centers on the psychology of personal minimums. Like most relationships, we will focus why we create them, why we commit them to paper [or not], when we fudge on them, what we learn from them, and what we hope never to again experience.

Interviews: For the interviews I asked starting questions and interchangeably used personal minimums and personal guidelines. The reason for this is some pilots initially thought when I spoke of minimums, I was referencing charted instrument approach minimums. The answers will be in their voice, the first person.

Questions

- Do you have a current set of personal guidelines or minimums for your flying?

- If yes, do you have them written down?

- If so, do you ever review them or alter/update them?

- What are the areas you consider when you think of your own minimums?

- Have you had a time where you cheated on your personal minimums?

- Has there been an experience in the airplane you would like to share that gave you a “pucker factor” that others might learn from?”

- Do you have a “hidden gem”, or learning tip, to share?

*[For the sake of this article, in their responses, I will simply use the word “minimums”]

K.W. Airline Captain CFI, Mooney owner

Looking down on Sedona, AZ

I got an instrument rating right after private and waited a bit to get my commercial. When thinking about personal minimums I divide things into three categories: the airport, myself, the airplane.

For the airport I am most concerned with surrounding terrain or weather conditions and my level of familiarity. My minimums would vary if say, terrain was high and my airport familiarity was low.

I am the most important part of the equation. I ask myself if I feel tired, what time of day is the flight and if I slept well. I pay attention to whether I am hydrated and eating well. I like to do airport homework a few days before. I consider destination and alternate airport approaches.

Airplane familiarity is something I consider every flight. When I am in my personal aircraft which I have owned many years, I know the ins and outs of the maintenance which factors in to my decision making. I have to say, I am very particular when it comes to fuel on board. My personal guideline is that I always land with 1.75 hours of fuel remaining.

When I was a private pilot did I not have things written down in terms of personal minimums. But I wouldn’t go to charted minimums with a 15 knot crosswind. Now that I am flying for the airlines, I have had to fly a variety of aircraft and the limitations are built in to our procedures.

Pucker Factor: I took off from Galveston some years ago. I’m not sure if I didn’t check for icing, or if icing wasn’t predicted (This flight was pre-ForeFlight and and other easy weather tools). It was typical Gulf Coast winter with 600’ overcast. I expected tops to be around 3,000’. It wasn’t that cold on the ground, maybe 45°F – 50°F. While climbing through the clouds at 1,500 ft I completely iced over. It took about 2 seconds. The windows were covered in frost and I couldn’t see anything. Fortunately, I was still climbing and speed was good. A really long minute or two later I saw sunlight coming through the frosted over windows. A few seconds after that all the ice melted off. It was gone as quick as it showed up. Lesson learned, always know where the freezing level is…even on the Gulf Coast.

Hidden Gem: I don’t have to fly anywhere, even as a pro-pilot. I have canceled a lot of personal flights when I feel I need to. There is no shame in sticking with your minimums and canceling a flight.

D.J., Commercial, Instrument, Mooney owner

Ice buildup on the Mooney wing.

I love flying, but I am a big sissy. As an instrument pilot, I have very high minimums. I don’t want to fly approaches down to charted minimums, my preference is to break out at 1,000 feet. I also wouldn’t launch on a flight to fly solid IFR. I have no backup vacuum so that is reasoning for wanting IFR to VFR on top.

I also consider the airport and weather conditions. For example, the cross-wind limitation is 11 knots from the POH. While I know I could do better on a long runway, for me that is a hard limit on a short runway. I am also particular with minimums about fuel, I always want to have 1.5 hours of fuel left on landing.

Another aspect of personal minimums is consideration of my health. If my sleep was not good night before, I won’t fly. If I am sick I wouldn’t fly. If I am emotionally upset I wouldn’t fly. I do find that flying is a stress reliever for mild stress. So determining my stress level is vital.

Pucker Factor: My airplane was loaded with medical personnel as I was headed to Mexico on a humanitarian flight. I encountered un-forecast icing over Julian [San Diego area] at 8,000 ft. The Mooney could not climb. Every surface was covered with the mixture of rime and clear ice and it flew like a slug [see photo above]. I immediately talked to ATC and let them know about the icing. Fortunately, within 20 minutes the ice had broken off, though we could hear it hitting the tail section.

Hidden Gem: Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. I took off Boise in dense fog. I accelerated down the runway in the fog, and once airborne I knew I would never do that again.

M.J. Airline Captain, Master CFII and Cessna owner

Over the Yellow Sea between Incheon, South Korea and Beijing, China

My best advice regarding personal minimums, is to write them down and take them seriously. Never change them for a single flight. If you change them for a current flight, they are not really a minimum. I suggest quarterly updates, perhaps in keeping with your landing currency [every 90 days].

During an instrument training and checkride you have to fly down to published minimums. After rated you will need to develop your personal minimums. Do you have one set of minimums for takeoff airport and landing airport [plus alternate]?

I have a lovely, and frequent passenger who isn’t a fan of bumps. Therefore, when I have passengers on board, I adjust my minimums for wind and turbulence. My maximum cross wind on landing is 10 knots for passenger comfort. It is important that I consider weather, my currency, proficiency, passenger comfort, day/night, and complete a runway analysis every flight.

Pucker Factor: I would describe my example of pucker factor by a story of one of my flights home from OSH. There was weather over the Rockies, starting right over Boulder, CO and continuing pretty much all the way to our Plan A destination at Grand Junction. My passenger was a fairly experienced CFI, but I was PIC for the trip. We discussed the weather issues (afternoon thunderstorms in the mountains) before takeoff on that leg and agreed on a couple points. First, we established a couple decision points, the first of which was over Boulder. Our criteria at that point was, could we see over the Divide adequately to attempt to cross Rollins Pass and continue, or turn around? Plan B was to divert to Ft Collins, where a friend had offered to put us up for the night. So, we knew what the concern was, had established our decision criteria, and had our options defined. We set another decision point near Eagle, CO, with a Plan C to land there and wait out the storm at a hotel for the night. As we approached Boulder (DP1), we assessed the situation and agreed that the pass looked good to continue, so we pressed on with Plan A and discarded Plan B. Did that again at DP2 and continued along. This portion was a little sketchier, but we both monitored the conditions and the way back to Plan C (landing at KEGE) remained good. In the end, we were able to continue with Plan A and had a very nice dinner at KGJT, and then a great flight on the final leg the next morning.

Hidden Gem: As pilots we are responsible for two types of environments: the strategic environment [on the ground planning]; and the tactical environment [in the air reality]. The strategic planning environment is measured, concrete and methodical. The tactical environment is situational, reality-based, and fluid. Make sure you take both into account on every flight.

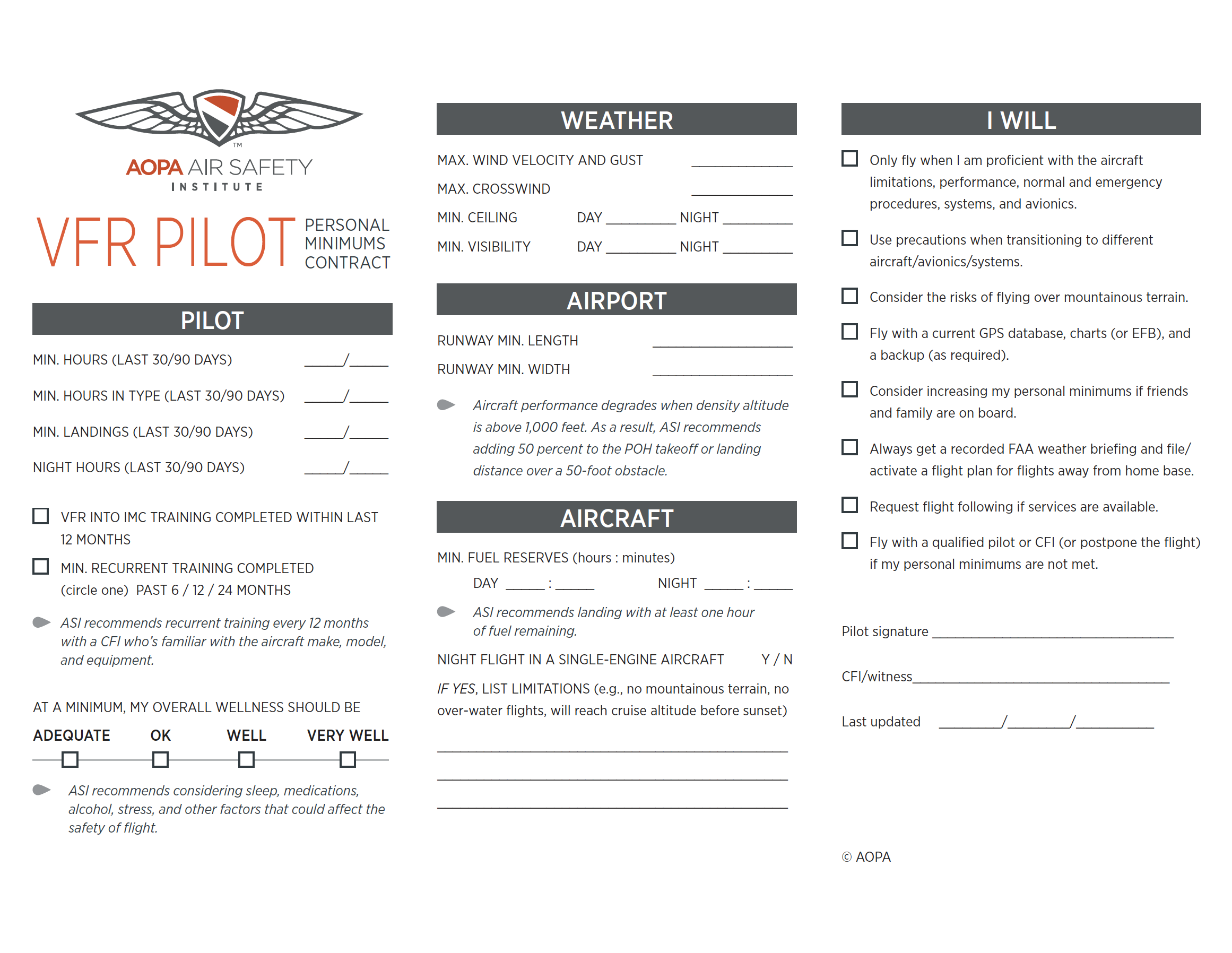

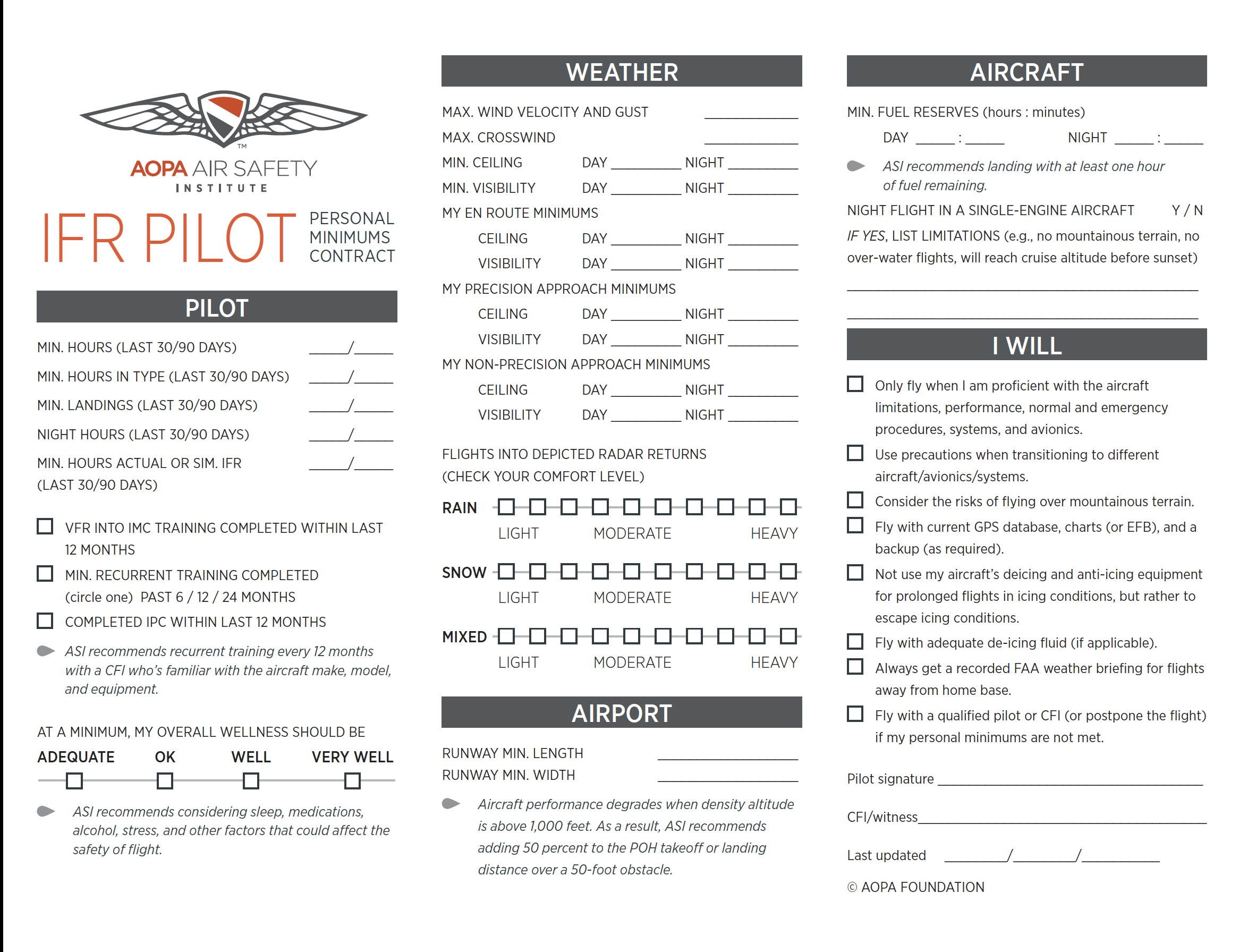

I hope you enjoyed this month’s installment. Please consider using one of the AOPA templates to write your minimums down whether VFR or IFR. If you have feedback about the interviews, please feel free to use the comment section below.

In the meantime, keep up with online safety seminars, join your state aviation association, and stay involved with your local airport. Make sure that you consider all aspects of minimums; airplane, pilot, and environment before you yell. “clear prop.”

My flight plans include 4S2 Hood River, Oregon, and KOSH, Oshkosh, Wisconsin. As my Dad used to say when we touched down, I am looking forward to another successful trip of “Haywire Airlines”